Paleoanthropology Society Poster 2025

Bigger is Not Better: Unexpected Relationship Between Prey Body Size and Macronutrient Composition in Eastern African Mammals

Authors: Isabel Heslin, Andrew Du, David Raubenheimer, Jessica C. Thompson

Digital Poster Download

References

- Andrews, P. (1990). Owls, caves and fossils: Predation, preservation and accumulation of small mammal bones.. The University of Chicago Press.

- Ben‐Dor, M., Sirtoli, R., & Barkai, R. (2021). The evolution of the human trophic level during the Pleistocene. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 175(S72), 27-56.

- Berbesque, J. C., Wood, B. M., Crittenden, A. N., Mabulla, A., & Marlowe, F. W. (2016). Eat first, share later: Hadza hunter–gatherer men consume more while foraging than in central places. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(4), 281-286.

- Brain, C. K. (2016). The hunters or the hunted?: An introduction to African cave taphonomy. University of Chicago Press

- Blumenschine, R. J., & Caro, T. M. (1986). Unit flesh weights of some East African bovids. African Journal of Ecology, 24(4), 273-286.

- Blumenschine, R. J., & Madrigal, T. (1993). Variability in long bone marrow yields of East African ungulates and its zooarchaeological implications. Journal of Archaeological Science, 20(5), 555-587

- Bunn, H. T., Pickering, T. R., & Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. (2017). How meat made us human. The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Diet.

- Butterworth, P. J., Ellis, P. R., & Wollstonecroft, M. (2016). Why protein is not enough:. Oxbow Books.

- Cordain, L., Eaton, S., Miller, J. B., Mann, N., & Hill, K. (2002). The paradoxical nature of hunter-gatherer diets: Meat-based, yet non-atherogenic. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 56(S1), S42-S52

- Cordain, L., Miller, J. B., Eaton, S. B., Mann, N., Holt, S. H., & Speth, J. D. (2000). Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 71(3), 682-692.

- Isler, K., & Van Schaik, C. P. (2014). How humans evolved large brains: Comparative evidence. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 23(2), 65-75.

- Leonard, W. R., & Robertson, M. L. (1994). Evolutionary perspectives on human nutrition: The influence of brain and body size on diet and metabolism. American Journal of Human Biology, 6(1), 77-88

- Malaisse, F. (2010). How to live and survive in Zambezian open forest: (Miombo ecoregion) (Updated ed.). Presses agronomiques de Gembloux.

- Malaisse, F., & Parent, G. (1986). Mammals of the Zambezian Woodland Area: A Nutritional and Ecological Approach.

- Ockerman, H., & Basu, L. (2014). BY-PRODUCTS | edible, for human consumption. Encyclopedia of Meat Sciences, 104-111.

- O'Malley, R. C., & Power, M. L. (2012). Nutritional composition of actual and potential insect prey for the Kasekela chimpanzees of Gombe National Park, Tanzania. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 149(4), 493-503

- Pitts, G. C., & Bullard, T. R. (1968). Some Interspecific Aspects of Body Composition in Mammals. Body Composition in Animals and Man, 45-70.

- Prendergast, M. E., Miller, J., Mwebi, O., Ndiema, E., Shipton, C., Boivin, N., & Petraglia, M. (2023). Small game forgotten: Late Pleistocene foraging strategies in Eastern Africa, and remote capture at Panga ya Saidi, kenya. Quaternary Science Reviews, 305, 108032.

- Speth, J. D. (2010). Paleoanthropology and Archaeology of Big-Game Hunting: Protein, Fat, or Politics? Scholars Portal.

- Speth, J. D., & Spielmann, K. A. (1983). Energy source, protein metabolism, and hunter-gatherer subsistence strategies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 2(1), 1-31.

- Stanisz, M., Skorupski, M., Bykowska-Maciejewska, M., Składanowska-Baryza, J., & Ludwiczak, A. (2023). Seasonal variation in the body composition, carcass composition, and offal quality in the wild fallow deer (Dama dama l.). Animals, 13(6), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061082

- Thompson, J. C., Carvalho, S., Marean, C. W., & Alemseged, Z. (2019). Origins of the human predatory pattern: The transition to large-animal exploitation by early hominins. Current Anthropology, 60(1), 1-23

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Elizabeth Grace Veatch for providing insight on small game, and Murphy Tu (MA student at Yale University) for assistance with statistical analysis.

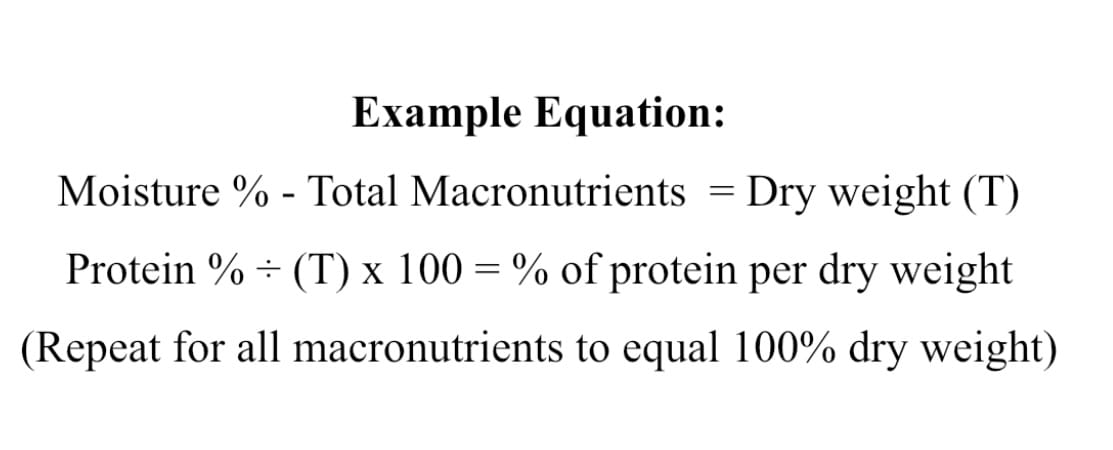

Equation used to standardize macronutrient proportions from published data:

Below is the poster formatted for the web:

Introduction

- Reconstructions of hominin diets often assume a positive relationship between proportional body fat and body size in prey species10

- The assumption that larger game are fattier has been fundamental in understanding early hominin hunting strategies and metabolic requirements (e.g., avoiding rabbit starvation)7, 8, 10, 19, 20, 22

- This assumption is based on estimates derived from non-African species and/or domesticated mammals, as proxies for wild African mammals17

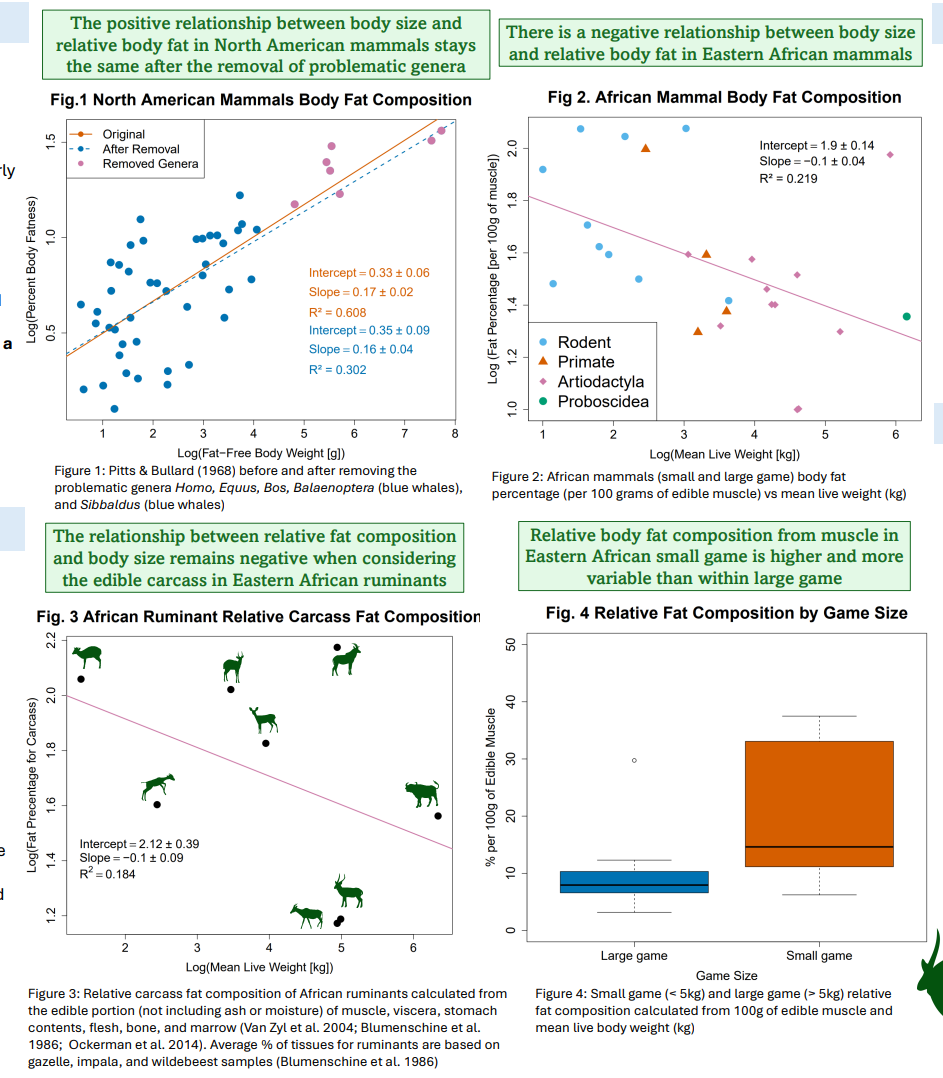

- We first test the validity that body size is a positive predictor of body fat in relative amounts of muscle in North American mammals

- Then we test this relationship in African mammals by compiling macronutritional data on edible muscle and on African ruminant carcass proportions

Methods

- Tested the positive relationship between body size and fat composition in North American mammals by removing the problematic genera (domesticated species, marine mammals, and humans)17

- Compiled relative nutritional and mean live body weight (LBW) data of contemporary Eastern African mammals inhabiting an open savanna-grassland environment from published datasets 14, 16

- Standardized protein and lipid percentages of African mammals to 100g of edible dry weight collected from muscle samples14, 16

- Calculated the relative proportions of edible fat available in African ruminants 5, 15

- Log-transformed and ran a linear model and regression to assess the relationship between body size and fat composition in African mammals

- Assessed the relative nutritional composition of small (< 5kg) versus large game (>5kg) in African mammals1, 4

Results

- After the removal of problematic genera, the positive relationship between body size and relative body fat in North American mammals remains supported

- The relationship between body size and relative body fat in African mammals demonstrates a slightly negative relationship indicating that as size increases, their relative body fat decreases

- When considering all edible components of a carcass, eastern African ruminants maintain a similar negative relationship

- Eastern African small game (< 5kg) is fattier per 100g of edible muscle than large game (> 5 kg)

Discussion

- The positive association in North American mammals may reflect latitudinal influences, such as increased seasonality and temperature variability at higher latitudes 21

- For understanding hominin evolution, African mammals offer a more suitable proxy for body composition analysis and dietary reconstruction

- Bigger is not necessarily better when it comes to consuming large quantities of fat in Eastern African mammals

- Relative nutritional content is the most reported nutritional data, assessing absolute composition may tell a different story • It is important to revisit the hypothetical diets of hunter-gatherers and earlier hominins with an adjusted framework that considers the data presented here 3, 9, 10

- Small game, often overlooked due to preservation bias, show higher fat content per 100g than large game 18, 20

Figures